Advocate Harnesses Grief to Create Change

By Luke Schmaltz, VOICES Editor

“Human progress is neither automatic nor inevitable…Every step towards the goal requires sacrifice, suffering and struggle; the tireless exertions and passionate concerns of dedicated individuals.” -- Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

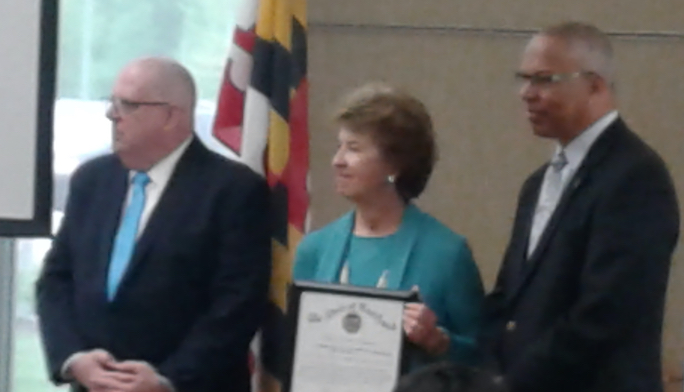

Barbara Allen is the founder of James’ Place, Inc., a foundation named for her son who died of a heroin overdose in 2003, after 22 years of struggling with substance use disorder (SUD).

Since then, Allen has blazed a prolific trail of advocacy, activism, education, and peer grief support. She is currently involved on a local, statewide, and national level – belonging to a total of 18 different groups. Allen applies her boundless energy in a wide circle of influence while being mindful of the grief stemming from her own personal losses. From her inner circle, she has lost a total of four people to drug overdoses, one to murder and one to suicide. Yet, she is undaunted in her mission to spread hope and awareness, wielding an uncanny ability to befriend anyone, anytime, in any setting.

Although she has been active for many years spreading awareness about SUD, Allen describes herself as a lifelong student. “To this day, my bottom line is there is so much more to learn,” she begins. “The more you know, the more you know you don’t know,” she says.

Inherent Behaviors

Tracing the pattern of SUD across her son’s lineage, Allen describes a mindset of denial within the family. “His father, his grandfather, his grandmother, and his aunts – on that side of the family – all used alcohol and prescription medication. Jimmy’s grandfather was a General in the military, and his attitude was, ‘I can’t have a problem, my parents were Baptists,’” she explains. “My mother-in-law told me they couldn’t have a problem because of her husband’s rank in the National Guard,” she says.

Amid this family culture of wholesale denial, Allen’s contrasting attitude went in stark opposition to that of her in-laws. “One of the things about me, is if there’s a problem, I am the type of person who turns right into it, faces it, and says, ‘All right, we’re going to get this thing done,’” she affirms.

The problems associated with raising a child who is struggling with SUD arose soon after Allen realized her son had a problem. “I learned when I got him into treatment at 14, it was already too late. Children form patterns, some not all, by the time they are four, five and six years old. By then, they are already habituated to behaviors they have seen in the family,” she explains. “I was really depressed, and it was a terrible time, because the therapist was telling me it was my fault. That if I hadn’t divorced his father, if I wasn’t a single mom, and if I didn’t work outside the home, it wouldn’t be a problem.”

As the grief over her circumstances set in, Allen was fortunate enough to find a psychiatrist, the head of the hospital, who was intent on avoiding judgment and giving his clients a fair shake. “He said to me, ‘here you’re going to learn the truth. You're going to have to learn because you don’t know yet,’” she explains. “My learning began at that time, and I was completely ignorant. At that point, I foolishly believed that I could get Jim into a program, and he would be fixed. Because at that time, it [SUD] was still not thought of as a disease but as a moral failing. All of a sudden, I went from [thinking] I’ve got it handled, to life turning to s#!t,” she explains. “Talk about a wakeup call.”

Defining Disease

Allen expands on this disparity when describing how she discusses SUD in the modern vernacular. Specifically, her directive is to expose and diminish the stigma associated with SUD. “When a parent comes into a meeting and they say, ‘Nobody told me,’ I say, ‘If your child had cancer, diabetes, heart disease, poor eyesight, would you not jump on the internet and try to find out everything you could about that [disease]?’ They always say ‘of course’ and I say, ‘well, you didn’t look up the fact that your child had a disease called substance use disorder,’” she says.

Allen’s intention to remove stigma from people suffering from SUD is demonstrated in her Shatter the Stigma initiative – a subset of James’ Place.

Better Emergency Outcomes

Across the breadth of her work, Allen has become involved in many areas of SUD, one of which is first responder and hospital emergency department protocol for patients who have overdosed. While Maryland, where she resides, has a standard operating procedure in place, most states do not. The overarching goal is to affect sweeping legislation which can establish a standard set of protocols for harm reduction through the use of an opioid antidote called Naloxone (Narcan).

Navigating Bureaucracy

In her efforts to influence leaders in state-level agencies, Allen is continually subjecting herself to the painstaking task of communicating the urgency of this movement to people who are hindered by bureaucratic red tape. “I was [recently] on a call with Maryland Insurance Administration, or ‘Missing in Action’ as I like to call it,” she begins, “My point in all this, is that it’s just so [expletive] painstaking, but things are changing systematically,” she says.

Allen continues to push for more legislative support in the form of funds for support services for those suffering from SUD as well as a more comprehensive adherence to the State of Maryland’s Good Samaritan Law, which says, “If you help someone in good faith who is in need of medical assistance from a drug or alcohol medical emergency, you and the person you help are immune from criminal prosecution.”

In It to Win It

Allen sums up her passion for her work with hard-hitting realism. “When you’re talking about something [intended] to save people’s lives, you have to talk about those people whose lives are not saved for lack of a support system – and that’s me,” she says. “My rule of thumb is I don’t get paid so I can’t get fired. So, my job is to tell you what you need to hear, not what you want to hear.”

Allen’s directive with bereaved parents is to demonstrate that there are many ways to work through the pain rather than staying locked in their grief. In her own experience of dealing with grief, she explains, “I know I am not doing all this so [that] I don’t feel the pain of those losses. I’m not hiding in it. I can talk with somebody, and they’ll tell me their story and I’m touched, and it reminds me of my story, and I’ll start tearing up. Maybe I’ll start crying and they ask if I’m OK, I’ll be like ‘Yeah, I’m fine – I’m grieving.’ That sometimes is the oxymoron of it all, ‘I’m fine; I’m grieving,’” she explains.

Allen has disciplined herself to take time for self-care. “There’s a lot of different ways,” she begins. “I’d rather be playing tennis, but my body is saying, ‘You’re out of your friggin’ mind.’ I’m getting older and that’s just the way it is. I like talking to people, I visit with neighbors, I joined my husband’s book club, we go to concerts and last week we went to the fair.” she says. “My husband jokes with me and says, ‘You’ve never met a stranger, have you?’ which is basically true”.