Is This Trauma or Grief?

By Joanna Bridger, SADOD Staff

When Barbara’s (name has been changed for privacy) son died from an overdose, she was constantly flooded with flashbacks. She could not escape replaying what had happened over and over for months on end, and she spiraled into pits of guilt and self-blame. Her night terrors kept her from sleeping, and as the weeks of little to no sleep continued, she felt like she was losing her mind. Her family and friends tried to support her but didn’t know how. When they told her she needed to get out of bed, go back to work, and think about her surviving children, she felt worse and more alone.

Losing a loved one to a substance related death is very often experienced as traumatic. The trauma of the death can complicate and, in some cases, get in the way of grieving. Grief is a normal and necessary part of life. Experiencing ongoing stress activation and symptoms of trauma does not have to be.

One common definition of trauma is “an experience that is too much, too fast, and too soon for a person to handle.” There are many reasons why substance related deaths are often experienced as traumatic. A recent study noted four significant (although not comprehensive) domains of the loss particular to substance related deaths. They are as follows:

- Constant preparedness that many people experience prior to their person’s death (anticipatory grief)

- Stigma - both public and self-induced stigma;

- Emotional overload - the complex and ambivalent emotions, such as anger, guilt and shock after the loss; and

- Complex relations and interactions with public services and personal social networks.[1]

Trauma is not wholly about the specifics of what happened to someone, as much as how it is impacting them in the present – showing up in their brains, bodies, lives, and relationships. Those reactions often result from the understandable increase in reactivity of the stress response. Overdose deaths are often experienced that way.

In many situations, trauma and grief become tightly interwoven. There are times when it is worthwhile to tease them apart to reduce the trauma reactions to allow people time and space to remember and grieve their loved one. Some loss survivors may fear this because the anger and anxiety of the trauma reactions may feel safer than the gulf of sadness of facing life without their loved one, or because they may consciously or subconsciously think that if they are not experiencing the trauma symptoms, that they are somehow forgetting about their loved one. However, most people find that when the trauma symptoms are reduced, they can remember and mourn their loved one in more authentic ways.

For most people, there is a combination of trauma and grief reactions, and they often change and shift over time. It is very common for reactions in the immediate aftermath for the grief to be overshadowed by the trauma of the loss.

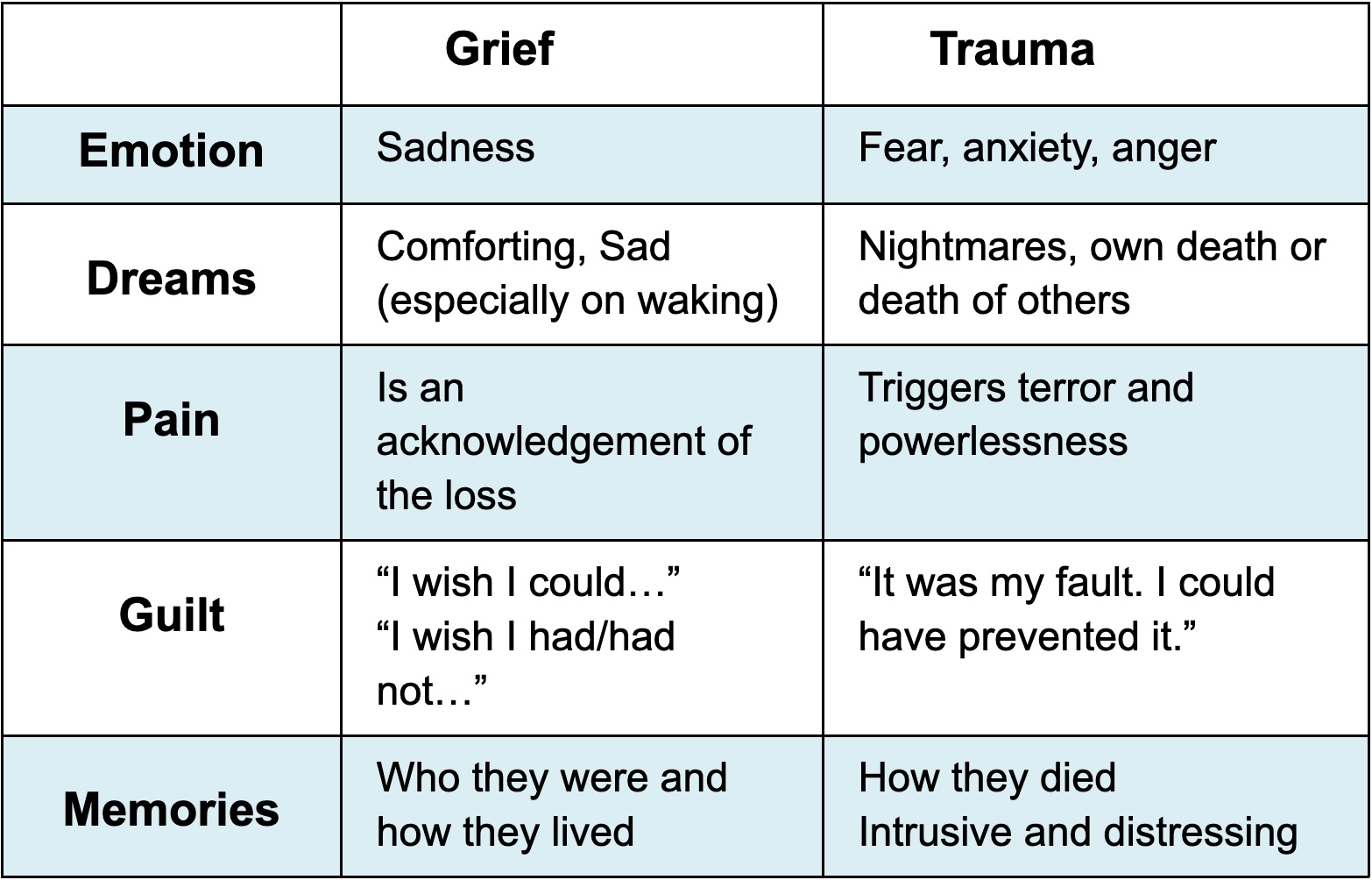

While these are necessarily generalizations, because every loss and the way every individual grieves is different, here are some domains to consider:

While there is always a benefit in finding support, when people are consistently experiencing reactions that are more on the trauma side, finding support that is specifically geared towards helping to reduce trauma reactions may be particularly important. There is a range of peer support programs, online forums, as well as therapists that can provide support specifically aimed at reducing the trauma symptoms. It can also be important to prioritize taking care of yourself physically and emotionally. Getting enough sleep, eating well, exercising, connecting with social supports (many things that people who are grieving may not be inclined to do), can help reduce the stress response leading to the trauma symptoms.

About a year after her son’s death, Barbara started attending a peer grief support group. She learned that she was not alone in the intensity of her grief, but also heard stories of people who were able to grieve who their loved ones were, after the trauma of how they died no longer eclipsed everything else. Barbara learned to use replacement memories of her son when the traumatic memories would arise and how to breathe, tap, and exercise to settle her nervous system. She started using the DBT nightmare protocol to address her night terrors and developed a sleep plan to help her body relax enough to let her sleep at night. Now Barbara feels like she is able to remember her son and those memories. While they will always be sad, they are not always debilitating. She has started to find ways to truly honor his memory.

** Suggested links to additional information on trauma:

National Council on Mental Wellbeing: How to Manage Trauma

Center of Disease Control: Coping with a Traumatic Event

Duke University: Coping After a Traumatic Death

SAMHSA: Tips for Survivors: Coping After a Disaster or Traumatic Event:

[1] Kristine Berg Titlestad, Sonja Mellingen, Margaret Stroebe & Kari Dyregrov (2021) Sounds of silence. The “special grief” of drug-death bereaved parents: a qualitative study, Addiction Research & Theory, 29:2, 155-165, DOI: 10.1080/16066359.2020.1751827

Joanna Bridger, LICSW is the Co-Director of the Frontline Service Provider Division of SADOD as well as the Founder and Director of Safety, Hope, & Healing Counseling & Consulting where she provides counseling, critical incident response, clinical consultation, organizational consultation, and training for families, schools, and organizations throughout Massachusetts and beyond.